Who is a member?

Our members are the local governments of Massachusetts and their elected and appointed leadership.

Patrick A. Tutwiler, Ph.D.

Secretary of Education

Commonwealth of Massachusetts

1 Ashburton Place, Boston

Re: Reform of Vocational School Admissions

Dear Secretary Tutwiler:

As Mayors, we have a front row seat to the effects of state education policy, for better and for worse, on the lives of our cities’ children. We write today to urge you to correct, once and for all, policies that we believe harm the prospects of children to reach their full potential, namely the state regulations that unfairly and perhaps illegally exclude students from the Commonwealth’s regional vocational high schools. Many of us set forth our concerns in the attached letter (please see below) to your immediate predecessor, dated January 31, 2020, in which we argued that the Department and the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education should abolish selective admissions at vocational schools and replace it with a lottery system. Unfortunately, that did not happen. The Department instead instituted a set of half-measures that have failed to end pervasive discrimination in vocational admissions.

Our 2020 letter explained how admissions policies at vocational schools have become unmoored from their original purposes. For years, vocational schools used selective admissions primarily as a means of ensuring that students who were being trained for jobs in an industrial economy could be counted on to safely operate heavy machinery. The introduction of the MCAS system in the 1990s, and the competition it incited among public schools, created an incentive for vocational schools to use their selective admissions authority to enroll higher performing students. To complement these efforts, vocational schools began to rebrand themselves as schools where students could become “college and career ready.” Superintendents and principals in comprehensive districts increasingly complained that regional vocational schools were “skimming” the best students and excluding others who did not perform well in a traditional classroom but who may have had an aptitude for and interest in a trade. Still others who were chronically absent because of an unstable homelife or who had minor disciplinary infractions were being left out.

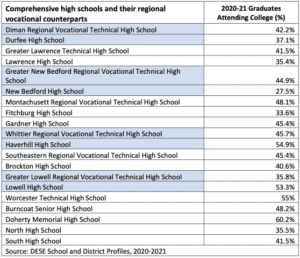

DESE’s data reveal that vocational schools accomplished what they set out to do. Despite their mission to provide students with an education for jobs in the trades and technical fields, vocational schools have built student bodies composed primarily of college track students. As the following chart depicts, the rate of college matriculation from several of the state’s largest vocational schools even exceeds that of their comprehensive high school counterparts, whose liberal arts curricula were designed for college preparation:

This inversion of education missions has resulted in a systemic mismatch of educational programming with the needs and aspirations of students. Many students interested in the trades find themselves unable to get into vocational schools, while many college track students who are sold on the vocational schools’ college prep marketing pitch, choose not to pursue careers in the trades they learned in high school.1 Among other troubling implications, this has exacerbated the shortage of qualified trades people in Massachusetts. In testimony before the legislature’s Joint Committee on Education last month, North Atlantic Carpenters Union Executive Director Tom Fisher stated that the percentage of vocational graduates who apply to the North Atlantic Carpenters’ apprenticeship program has fallen to 10%, an all-time low. Of the union’s current 1,200 apprentices, only 100 are graduates of vocational schools. This is happening during a period in which vocational schools have seen steady enrollment. The solution proposed by the defenders of selective admissions is simply to enlarge the enrollment of vocational schools so that they can serve more students. Aside from the significant capital costs of expanded school facilities this would require, this still would not address the incentive for vocational schools to use their selective admissions authority to exclude lower performing or attending students.

As our 2020 letter pointed out, perhaps the most troubling byproduct of selective vocational admissions has been its exclusion of students from protected classes, including students of color and special needs students. The starkest gaps have been among English Language Learners, the children of recent immigrants who commonly are challenged not only by language barriers, but by a transient homelife, interruptions in their formal education, and the various impediments generally associated with poverty. Our letter set forth DESE data showing that at several of the largest vocational schools, the enrollment of ELL is so low that it could not conceivably be justified by any valid educational purpose.

We argued that the only effective solution to eliminate these disparities would be to implement a “qualified lottery,” in which eligibility to enter the lottery would be the same as that for charter schools, that is, residency in the district and eligibility to graduate from eighth grade. We predicted that if DESE did anything less, the problem would persist, and it would likely prompt a civil right lawsuit.

DESE’s Attempt at Reform

By the time of our letter, DESE had begun to publicly acknowledge a problem with vocational admissions. Weeks earlier, it had informed six regional vocational districts that it had “identified enrollment discrepancies for various subgroups,” including students with disabilities, low-income students, students of color and English Language Learners. DESE also issued a veiled warning to those schools, informing them the Board planned to reform its vocational admissions regulations, and suggested that in the meantime the schools might consider voluntary changes to their admissions policies.

In June 2021, the Board adopted regulations that tweaked its admissions regulations. It mandated that vocational schools submit their admissions policies annually to DESE for review, and that DESE would monitor whether disparities persisted. The Board also barred schools from considering minor disciplinary infractions or excused absences. The Board otherwise left selective admissions intact, and offered the following guidance that merely stated essentially what federal law already required: “… Vocational schools and programs that use selective criteria shall not use criteria that have the effect of disproportionately excluding persons of a particular race, color, national origin, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or disability unless they demonstrate that (1) such criteria have been validated as essential to participation in vocational programs; and (2) alternative equally valid criteria that do not have such a disproportionate adverse effect are unavailable.” Rather than seizing responsibility for the problem, DESE left it up to vocational school boards, which had little incentive to relinquish their authority to select higher performing students, to come up with their own admissions policies, subject to a largely undefined review by DESE.

The result of the Board’s milquetoast reforms has not surprised anyone. Of the 28 regional vocational school districts, only Assabet Valley Regional and Worcester Tech adopted a lottery admissions policy. The others kept selective admissions in place, using the same criteria, namely academic performance and attendance, that have been used to exclude students who could have benefited from what the schools have to offer.

The Board’s Actions Failed to Solve the Problem

Some three-and-a-half years later, what we predicted has come to pass. DESE’s attempt at reform has yielded little discernible improvement in eliminating disparate admissions outcomes. And a statewide coalition of civil rights groups, labor unions, school districts and business organizations have rallied behind a federal civil rights action against the Department, which alleges that the vocational admissions policies have discriminated against protected classes of student applicants.

It is unmistakable that the Board’s new regulations have failed to remedy the disparities among protected classes. In fact, in some notable respects, the problem has become worse. For instance, the gap between the acceptance rate between white students and students of color at vocational schools widened from 2022 to 2023. The acceptance rate among low-income students fell from 60% in 2022 to 54% for 2023.

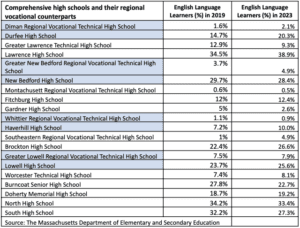

The situation with ELL students remains a glaring, if not tragic problem. The chart below depicts the ELL enrollment at the largest vocational schools and their comprehensive high school counterparts in the 2019 academic year, which we included in our 2020 letter, and this past year. It shows no material closing of the enrollment gap. It is so vast that it cannot be justified on the grounds of any legitimate educational purpose.

The problem persists because vocational schools still exclude students based on academic performance, as well as on attendance, which itself is a proxy for academic performance. As we noted in our letter, academic performance in middle school is not a predictor as to whether a student may benefit from a vocational education. Many students who have not excelled in a traditional classroom in middle schools have thrived in a vocational high school, yet the admission of students who fit this profile are being crowded out by the admission of college-track applicants. Using attendance as a selection criterion has an unavoidably disproportionate impact on students living in poverty. As 2022 Guidance for Attendance Policies states, “Children living in poverty are more likely to be chronically absent due to life circumstances such as lack of access to health care, housing insecurity, and unreliable transportation.” It is no surprise that the use of attendance is perpetuating the exclusion of students who could benefit from a vocational education. The reality is without the neutrality inherent in a lottery, discrimination in vocational admissions will persist.

Conclusion

At this point, there is little dispute that a problem exists. For over a decade, the Board and the Department have known about the profound unfairness of vocational admissions, yet they have been unwilling to take on the problem. Their inaction has prompted the possibility of legislative intervention, as well as a civil rights lawsuit, one which we believe the state will lose. Rather than wait for a court to tell the Department to institute a lottery system, the Department should seize its responsibility and act now, before more children are unfairly denied the opportunity to pursue an education that meets their needs and aspirations.

Jon Mitchell

Mayor of New Bedford

Geoffrey C. Beckwith

MMA Executive Director & CEO

Katjana Ballantyne

Mayor of Somerville

Edward Bettencourt

Mayor of Peabody

Paul Brodeur

Mayor of Melrose

Michael Cahill

Mayor of Beverly

Gary Christenson

Mayor of Malden

Paul Coogan

Mayor of Fall River

Carlo DeMaria Jr.

Mayor of Everett

Cathleen DeSimone

Mayor of Attleboro

Scott Galvin

Mayor of Woburn

Joshua Garcia

Mayor of Holyoke

Kassandra Gove

Mayor of Amesbury

Thomas Koch

Mayor of Quincy

Nicole LaChapelle

Mayor of Easthampton

Jeannette McCarthy

Mayor of Waltham

Jared Nicholson

Mayor of Lynn

Michael Nicholson

Mayor of Gardner

Shaunna O’Connell

Mayor of Taunton

Dominick Pangallo

Mayor of Salem

Sean Reardon

Mayor of Newburyport

Sumbul Siddiqui

Mayor of Cambridge

Robert Sullivan

Mayor of Brockton

Roxann Wedegartner

Mayor of Greenfield

Greg Verga

Mayor of Gloucester

Arthur Vigeant

Mayor of Marlborough

CC:

Her Excellency Maura Healey, Governor of the Commonwealth

The Honorable Kim Driscoll, Lieutenant Governor of the Commonwealth

The Honorable Jason M. Lewis, Senate Chair, Joint Committee on Education

The Honorable Denise C. Garlick, House Chair, Joint Committee on Education

Katherine Craven, Chair, Board of Elementary and Secondary Education

Members of the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education

Jeffrey C. Riley, Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education

Thomas Scott, Executive Director, Massachusetts Association of School Superintendents

Glenn Koocher, Executive Director, Massachusetts Association of School Committees

Max Page, President, Massachusetts Teachers Association

Beth Kontos, President, American Federation of Teachers – Massachusetts

Attachment: Letter to James A. Peyser and Jeffrey C. Riley, dated January 31, 2020