Who is a member?

Our members are the local governments of Massachusetts and their elected and appointed leadership.

Mass Innovations, From The Beacon, December 2022

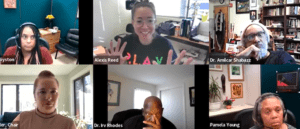

Amherst’s African Heritage Reparation Assembly meets online regularly, often weekly, to discuss its work. Pictured during the Nov. 7 meeting are (top row, l-r) Assistant DEI Director Jennifer Moyston and assembly members Alexis Reed and Amilcar Shabazz, and (bottom row, l-r) assembly members Michele Miller and Irv Rhodes, and DEI Director Pamela Nolan Young.

As the second community in the country to establish a fund addressing the historical and ongoing damage of structural racism, the town of Amherst has since been examining what a reparations program could look like at the municipal level.

In December 2020, the Town Council passed a resolution to “end structural racism and achieve racial equity for Black residents.” In June 2021, the council created a reparations fund, and established a seven-member African Heritage Reparation Assembly to study and develop proposals. And this past June, the council committed to placing $2 million into the fund over the next decade.

Far from a new concept, the demand for reparations efforts gained greater urgency after the 2020 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The work involved, however, causes communities to confront a painful, centuries-old history of racial injustice, legal questions about how to structure reparations, and financial pressures surrounding any reparative programs that a city or town does pursue.

“Municipalities have a lot of demands on very limited resources,” said Pamela Nolan Young, who became Amherst’s first director of diversity, equity and inclusion in July. “So as a community, it takes, I think, first, a commitment, a moral and ethical commitment to take on this issue, and then secondly, a commitment of finances.”

Reparations efforts have been growing around the country and in Massachusetts, as advocates say that reparations are needed not just at the federal level, but also at the local level.

Evanston, Illinois, was the first municipality to set up a reparations fund, followed by Amherst. Several other Massachusetts communities have begun to approach the question, including Northampton, where advocates are asking the city to create a reparations commission. The Boston City Council may soon vote on creating a body to study reparations.

In Amherst, a grassroots group, Reparations for Amherst, grew from the aftermath of Floyd’s death and began documenting harms inflicted on the Black community in Amherst. Its work influenced the council’s December 2020 resolution, which listed numerous harms, including the vote by selectmen in 1762 to order free Black residents out of town, the inability of UMass Amherst’s first Black faculty member to obtain housing in 1948, and covenants banning property sales to Black buyers.

Town Councillor Michele Miller, the assembly’s chair and co-founder of Reparations for Amherst, said the resolution’s specificity was deliberate.

“We needed to lead this with data,” said Miller, who joined the Town Council after the resolution was adopted. “In order for people to embrace this and support this, we really needed to be as specific as possible about what occurred in our town, as opposed to just generally throughout the country.”

The assembly’s work

By charter, Amherst’s assembly must include a Reparations for Amherst member, and six Black residents selected by the town manager’s office. One appointee, Debora Bridges, is a sixth-generation Black and Indigenous Amherst resident whose ancestors were heavily involved in the town’s history. Her family’s contributions to Amherst, however, didn’t stop her fourth-grade teacher from asking her, “What does it feel like to be a slave?” in front of her class in 1961, or from seeing Confederate flags in classmates’ vehicles.

“I want to inspire the youth to know about the ancestors, my ancestors, other ancestors that may have been misrepresented,” Bridges said. “That needs to be out there. That’s why I’m there.”

Bridges and her colleagues will recommend possible reparations expenditures. In its June 2022 vote, the council agreed to transfer up to $205,000 from free cash into the reparations fund annually for a decade. Though the town doesn’t earmark the funds specifically, the amount would reflect its cannabis tax revenues, to acknowledge the disproportionate racial harms caused by drug enforcement.

In addition, the assembly has had the UMass Donahue Institute review 2020 census data for insights about Amherst’s Black community, which makes up about 5.6% of the town’s population of 39,000. Using that information, and a signup portal on the town’s Engage Amherst website, the assembly is reaching out to Black residents and plans to survey them for their feedback. It is also considering a broad range of programs, including working with the UMass Clean Energy Extension, to explore the creation of solar projects to benefit the Black community financially.

The assembly also held its first listening session with residents in late October. Amilcar Shabazz, an assembly member and professor in the W.E.B. DuBois Department of Afro-American Studies at UMass Amherst, said this process allows people to process their experiences and tell their stories.

“This process can evoke a lot of deep reflections in a community, about things that have happened in their lives, things that have come down for them as trauma through generations,” Shabazz said. “It does it for me.”

By June 2023, the assembly must file its final report, with plans for ongoing funding streams, recommended eligibility criteria and possible future actions. The council will then review the report and decide which actions to take, including whether to appoint a successor body to make funding recommendations.

“The hardest things are coming up in the next six to eight months,” said assembly member Irv Rhodes. “And that is, identifying and documenting the harm, identifying those who were harmed, outlining a process for all of those, outlining a process for looking at how the funds will be distributed, and to whom they will be distributed, and for what it will be distributed.”

Forms of reparations

Nationally, resistance to reparations has often stemmed from the misconception that reparations involve only direct cash payments to individuals. But reparations also involve broader programs that benefit the larger community, attempt to repair past harms, and create a more equitable system for everyone going forward.

“I think the word reparations sounds foreign to some people, but it’s gaining currency as people become more familiar with it,” said Town Manager Paul Bockelman. “There’s a giant educational piece to this.”

As examples, assembly members said possible reparations could include a community center or cultural center, genealogical resources for Black residents, youth empowerment programs, programs connecting young people with local Black history, greater access to free and reduced lunches, and fully subsidized athletics and after-school activities for Black students in need.

Amherst officials said no decisions have been made yet about direct reparations payments, though some expressed concerns that direct payments would prove to be more politically and legally challenging to pursue. For example, special legislation would be required if residents were to receive direct payments, Bockelman said.

Town Councillor Anika Lopes, the daughter of assembly member Bridges, said she doesn’t want to minimize residents’ immediate, short-term needs, but she would want to emphasize programs focused on long-term transformation. She said programs bettering people’s lives and achieving equity “seem to be the most concrete avenues that are wide open and also the most lasting and significant repair that we can give at this point.”

For more information about Amherst African Heritage Reparation Assembly, contact Town Councillor Michele Miller at millerm@amherstma.gov or visit the Assembly’s page on the Engage Amherst website.