Who is a member?

Our members are the local governments of Massachusetts and their elected and appointed leadership.

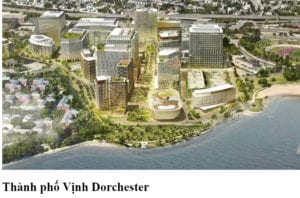

Boston Planning and Development Authority website pages can be translated into dozens of languages, including the Vietnamese-language page here describing the proposed redevelopment of the former Bayside Expo Center site in Dorchester.

Seeking to give residents a greater voice in its work, the Boston Planning and Development Agency has been expanding access to public meetings and documents in a range of languages.

On March 11, the agency’s board is expected to adopt a language-access plan, formalizing what the agency has already put into practice. For its development review and planning work, the agency has been providing interpreters for hearings and translations for key documents in the major languages of city neighborhoods.

The language-access efforts reflect the demographic shifts Boston has experienced in recent decades and the agency’s desire to give residents more input in neighborhood changes, said Boston Planning and Development Director Brian Golden.

“If there’s a significant population that does not speak English, we need to address that because otherwise they’re in the dark,” Golden said, “and we want to make sure that people understand exactly what’s being presented, what’s being considered in their neighborhood, so that they have an opportunity to weigh in on it, so that their voice is meaningful, their voice is heard.”

Over the years, the agency has been expanding outreach efforts to communities including immigrants and people with disabilities. In a city of almost 700,000, more than 114,000 residents report that they speak a language other than English at home and say they speak English “less than very well,” according to agency statistics.

The agency had long been providing translations on a case-by-case basis, but decided to formalize the practice following the two-year review of the Suffolk Downs project, which involves the redevelopment of the former racetrack into a mixed-use neighborhood. Golden said the agency had increased the language work during that process, providing translations mainly in Spanish but also in Arabic. Requiring translations universally removes the guesswork for both developers and the agency, he said.

With the agency holding virtual meetings during the pandemic, people who need real-time translations can choose among different Zoom language channels, said Sonal Gandhi, the agency’s deputy chief of staff. Live interpreters provide the translations, she said.

Visitors to the agency’s website can click on “Translate Page” and have Google Translate convert the text into more than 100 languages, and the agency offers technology for people with visual impairments. The agency also requires translation of key documents related to projects. Summaries or fact sheets are provided for documents that are too cumbersome or expensive to translate.

The agency’s research department reviews census data and regularly updates its list of widely spoken languages in each neighborhood, Gandhi said. For citywide events and documents, the agency currently lists five top non-English languages: Latin-American Spanish, Simplified Chinese, Haitian Creole, Vietnamese and Cabo Verdean Creole.

The agency expects the translation and interpretation services will cost roughly $200,000 a year for its own planning activities, but developers must cover the costs for their projects. The agency maintains a list of vetted interpreters, Gandhi said.

Gandhi said the agency is fine-tuning its interpretation work for virtual meetings, while exploring options for when the agency resumes in-person hearings.

Golden said the agency’s efforts to expand access have received significant support from outgoing Mayor Martin Walsh, and he believes the next administration will provide similar support. Both the city and developers have abandoned the top-down approaches that dominated planning and development in decades past and locked whole communities out of the discussion.

“We think you get the most good when neighborhoods sign up for what you’re trying to do, whether it’s a new planning exercise or a development that’s being proposed in a neighborhood,” Golden said. “Everybody wins if there is public buy-in for what you’re proposing.”