Who is a member?

Our members are the local governments of Massachusetts and their elected and appointed leadership.

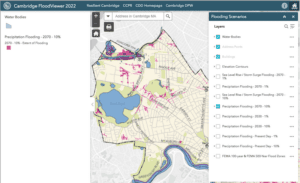

The Cambridge FloodViewer is a tool for property owners and developers to see the extent of flooding threats to every property in the city.

In an effort to mitigate the impacts of climate change, the city of Cambridge is taking a multi-pronged approach to resiliency, looking at the impacts of flooding, heat and emissions.

The city’s work is part of a broad Resilient Cambridge Plan that was released in 2021. The plan maps out 24 strategies in four categories — closer neighborhoods, better buildings, stronger infrastructure, and a greener city — to drive the work of the city to reduce the risk and severity of climate change with an emphasis on using the best available information to do so.

“We always talk about flooding in terms of reducing the severity and frequency — not eliminating,” said Public Works Commissioner Kathy Watkins. “You’re trying to make it so low-lying areas are less impacted by flooding and also working with residents to say, ‘OK, if you are flooded, what are the steps you can take?’

“That is where the infrastructure and zoning conversations really line up in terms of trying to do this multi-pronged approach at the same time.”

For its 2015 Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment, the city worked with climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe to develop rainfall projections for 2030 and 2070 using climate change data, not past events. (The state has recently developed updated projections using the same methodology.)

The projections are available in a useful FloodViewer tool, where property owners and developers can see projected flood levels for every property in the city, enabling them to make more informed decisions.

The city has made significant investments in underground storage tanks to help mitigate the impact of flooding in neighborhoods. Already in place are 12 tanks that can hold more than 2 million gallons of water.

The city is working with the Resilient Mystic Collaborative to address coastal flooding concerns related to two dams that are expected to be able to provide less protection by 2040 in light of predicted sea level rise and an increase in powerful coastal storms. Failure of the dams, Watkins said, would impact the Mystic River and Alewife Brook.

“Alewife feels really far away from the ocean, but by 2070 if we don’t do anything you would expect to see that area have salt water impacts every two years,” Watkins said. “If we can stop the water at [the dam] locations then you can protect the areas behind it.”

Regional intervention efforts could reduce future flooding risk in 11 additional communities, she said. The effort recently received a Federal Emergency Management Agency grant to continue the work.

“Cambridge really benefits greatly from these interventions, but none of them are within Cambridge so the conversation about this really requires a different approach,” Watkins said. “As we really look at impacts of climate change, knowing that each individual municipality can’t work on these things alone, it really takes a much more collaborative effort.”

Cambridge has also been working in partnership with the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority and the city of Somerville to plan for significant improvements to reduce combined sewer overflows, building on work already underway in part to improve water quality in the Charles River and Alewife Brook. The city is again looking to projected future rainfall levels to establish a future “typical year.” The effort has already seen a 98% reduction in combined sewer overflows into the Charles and 85% into Alewife.

“We know the work we’ve done to date has been really effective,” Watkins said. “We also know there is more work to do.”

Cambridge also has new resiliency zoning requirements taking effect this month that will require new buildings and those undergoing major renovations to factor in climate change projections. The new zoning provides clarity to the process for property owners, Watkins said.

In June, Cambridge adopted a new net-zero amendment to its Building Energy Use Disclosure Ordinance, mandating that non-residential buildings reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2035 for large buildings (larger than 100,000 square feet) and 2050 for mid-size buildings (100,000 square feet or smaller).

The city is working to mitigate the impacts of heat through its Urban Forest Master Plan, looking to grow the urban tree canopy and implement strategies that allow current trees to thrive. A recently opened park in East Cambridge — an area that used to be a gravel lot for construction staging — now has more than 400 trees. The purpose of the park evolved from plaza to urban forest to meet the city’s priorities.

“We are trying to emphasize the value of planning,” Watkins said. “It’s really critical to have those processes that set the stage.”