Who is a member?

Our members are the local governments of Massachusetts and their elected and appointed leadership.

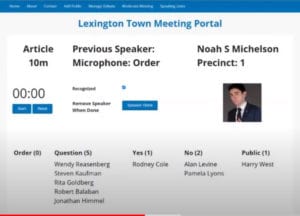

Built by Select Board Member Joe Pato, this Lexington Town Meeting portal allowed the moderator and members to keep track of who was speaking, and who was waiting to speak, during the virtual meeting.

In 1775, Lexington helped set the stage for the fledgling American democracy. This month, the town broke new democratic ground by holding the state’s first virtual Town Meeting.

Using a combination of computer applications, the town began its four-night representative Town Meeting on June 1 for nearly 200 members. The town wanted to meet remotely to protect the health of its Town Meeting members, many of whom fall into higher-risk categories for COVID-19.

“Today Lexington is once again making history,” Town Moderator Deborah Brown said as she called the meeting to order. “I dare say this will be the Zoom webinar heard ’round the Commonwealth.”

Lexington’s virtual Town Meeting involved weeks of planning, accelerated technological development, nearly a dozen training sessions, and substantial staff engagement. While the event saw some high-tech hiccups, the process succeeded in its goal of seeming ordinary, said Select Board Member Joe Pato.

“I think it’s been going just like a normal town meeting, which is what we were aiming for,” Pato said.

Even with a pared-down warrant, he said, the proceedings stretched into a second week, on June 8.

“We like to talk and debate, and the system has made it easy enough that people are doing it,” he said. “They’re not dissuaded, they’re not put off. We’ve had robust debates.”

Pato, a retired research computer scientist who helped build the meeting’s online portal, said the process functioned well from a technology perspective. In its new format, Town Meeting experienced the same low-tech issues that many towns face – complicated warrant articles, amendments and controversial topics. In particular, Town Meeting reversed a vote approving funding for a new police firing range, against the backdrop of national protests over police violence and local objections to the project.

About 190 of the 197 Town Meeting members attended the first night, with participation staying in the 170s or 180s on subsequent nights, Pato said. Lexington’s quorum is 100.

“Most Town Meeting members who have contacted me or have spoken publicly have just been relieved that they were able to participate in a Town Meeting this year and feel like it was a real meeting,” Pato said.

Technology and preparation

Lexington Town Meeting used three applications: Zoom, an online voting program from Option Technologies, and a town meeting portal built by Pato. To prevent hacking, the town created authenticated accounts allowing only meeting members and authorized personnel to access the programs. Members of the public were able to watch the proceedings online or on local cable, and could submit statements electronically to be read aloud.

Beforehand, the town held roughly a dozen trainings, which included separate sessions for each of the nine precincts, a makeup session, and a mock meeting involving the full group. People who needed additional training also received one-on-one help. Pato said the preparation paid off. About a third of the members had experienced technical problems during the training sessions, but only about 5% had problems during the meeting itself.

On the first night, the meeting started about 15 minutes late, while members logged in officially for the first time. Some members had problems toggling between Zoom and the other meeting applications. As with any online meeting, people would sometimes forget to unmute themselves while speaking, and the sound quality could waver.

Pato said that the town had three or four IT staffers helping members during the meeting. People could report problems through the Town Meeting online portal, or call into a help line.

“From the staff perspective, I couldn’t be happier with the way they’ve worked at this and taken to heart their role in making representative democracy work,” Pato said.

Every Town Meeting member had computer access, but one woman’s operating system didn’t support Zoom, so the town arranged a workaround: The woman would watch the proceedings on television, and a staff member would call to get her votes and report them to the moderator.

The system worked for the first two nights. On the third night, though, the woman’s television also stopped working. So the staff member picked up the woman, and drove them both back to her house. With masks and a 6-foot distance, the woman used the staff member’s computer, and the staff member drove her home at about 11:30 that night.

“Our goal was: no Town Meeting member left behind,” said Brown, the moderator.

Lining up

At a traditional Town Meeting, members would line up behind different microphones, depending on whether they would be speaking for or against an article or had questions. Pato’s program recreated that experience online.

“He wrote this really wonderful queuing function where Town Meeting members would basically put themselves in one of those speaking lines,” Brown said. “And then I had a dashboard that I could look at and recognize those people at the appropriate times.”

To instill confidence in the process, Brown said, officials proceeded slowly, to give people time to navigate among their computer applications. They allowed members to give voice votes when their voting apps didn’t work, and displayed votes on the screen, so that members could speak up if they saw mistakes.

“I mean, this could have gone any number of ways, right?” Brown said. “People could have felt just so uncomfortable with this that it could have affected their approach to it, their attitude, but everyone had such a positive attitude about it.”

Lexington may be first, but it isn’t alone. Other communities, including Winchester and Brookline, are also holding remote town meetings this month.

On June 5, Gov. Charlie Baker signed legislation giving representative town meetings the ability to meet virtually. As Lexington waited for that legislation to work its way through Beacon Hill, the town had already anticipated taking other legal steps to protect its Town Meeting, including petitioning the Legislature to have its meeting results accepted by the state.

“The state statutes governing Town Meeting were written long before anyone could have contemplated this type of meeting,” Brown said, “and so the language that’s used that suggests a ‘convening’ has been interpreted by some to clearly mean convene in person, and that’s why we had to seek the legislation. But I think there will be some interesting conversations about this.”

The legislation allowing for remote representative town meetings applies only to the current COVID-19 emergency period. Lexington officials anticipate they will also need to meet remotely for a special Town Meeting in the fall, given concerns that the COVID threat will persist for months to come.

Both Brown and Pato envision possible future uses for virtual meeting technology. They said it could allow for greater participation among people with disabilities, people who are ill, and younger residents who might want to serve but who have small children at home.

For this Town Meeting, officials worked with the town’s disability commission to ensure public access to the meeting, Brown said. The proceedings were closed captioned, and officials adjusted fonts and contrasts to make sure the online content was readable.

Long-term use of virtual meeting technology, Pato said, would require additional legislation and significant public discussion. But the technology can make Town Meeting more inclusive, he said.

“It opened the door to say, ‘we can have participation using this electronic medium in a way that is parallel and comparable to the in-person portion,’” Pato said. “I missed seeing people in person, but I think there is a lot of potential to make it so everyone is fully enfranchised in the future.”