Who is a member?

Our members are the local governments of Massachusetts and their elected and appointed leadership.

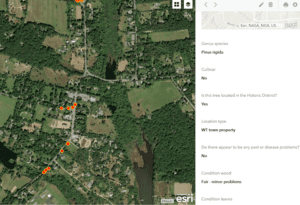

West Tisbury uses online mapping to inventory trees in its Historic District.

In the face of climate change, West Tisbury has established a tree committee, invested in new tree plantings, and developed plans to protect and expand its tree canopy.

The Martha’s Vineyard town of roughly 3,500 is confronting the effects of an aging tree canopy dominated by invasive maples. To reverse the trend, West Tisbury formed an eight-member Tree Advisory Committee in 2021, and in April, Town Meeting approved more than $19,000 to plant 16 new trees. The committee is currently overseeing the digital mapping of trees in a prominent section of town to guide future decision-making around its tree population.

Tim Boland, the committee’s chair and executive director of the local Polly Hill Arboretum, said the changes recognize the importance of trees as a municipal resource.

“We have roads, we have lights, electricity, we have maintenance of our town infrastructure,” Boland said. “This would be an investment in what I call ‘biological infrastructure’ — living things that really kind of make a town. … As we move forward, that’s what we really need to look at, that investment as well.”

Like other Northeast communities, West Tisbury once had a large supply of American elm trees that largely succumbed to Dutch elm disease by the 1950s, Boland said. Norway maples took their place, Boland said, because they could handle tough soils and needed little water and maintenance. Only later did people discover the extent of their invasiveness. And because more than 50% of the street trees are Norway maples of a similar age, they are dying off at the same time, officials said.

Municipal trees face numerous threats beyond old age and disease, said Jeremiah Brown, West Tisbury’s tree warden. Overly aggressive trimming around power lines, the proximity of parking lots to trees, and the salt and spray from snow plowing all contribute to poor tree health. He estimates that he removes about six to 10 trees annually.

“By nature, the trees that are close to humans — they don’t do as well as if they were in nature and being left alone,” Brown said. “So I guess that would be most of the challenge, trying to not have humans do bad things to trees that they all do.”

Last summer, West Tisbury began taking an inventory of trees in the 3.7-square-mile Historic District, using a phone app to load tree data into a digital map with information about each tree’s health, visual defects, diameter, height, and age, Boland said. The map will include sites for future plantings, and he sees the possibility of mapping other parts of town later on.

To avoid past problems, the town will plant a mix of trees, with an eye toward a changing climate. Officials said they can’t predict how intensifying weather will affect trees adapted to current conditions, but they’re hoping that tree diversity will help make the overall canopy more resilient.

West Tisbury’s new trees will include shadbush, flowering dogwoods, beetlebung, hop hornbeam, Atlas cedar, American basswood, scarlet oak, and two disease-resistant elms. Brown said he hopes to get the trees planted by October.

In the future, Brown said he would seek a budget for 10 to 12 new trees a year, to replace the trees he typically removes annually and help catch up from previous years’ losses.

“We want to have a lot of trees in town,” Brown said, “and people to be proud of it.”